In the late 1960s, Singapore was experiencing a vibrant period of growth and development.

The island state had just gained its newfound independence after being abruptly ousted from the Malaysian Federation on 9 August 1965. To ensure the country’s survival, the Singapore Government began investing heavily in the country’s manufacturing sector to create jobs and attract foreign investment.

This period of rapid industrialisation continued well into the 70s. However, as a small and developing country, Singapore soon began to experience labour shortages in certain sectors.

For sectors that were doing well, such as electronics manufacturing, employers could pay their workers up to 20 per cent more to attract and retain workers. However, wages remained largely stagnated for some workers, such as those in the civil service.

Additionally, the Government also became concerned that wage increases in the manufacturing sectors would overtake the country’s national productivity gains. The increase would have led to higher business costs, making Singapore less competitive globally.

Thus, to stabilise the labour market, then-Finance Minister Hon Sui Sen proposed the establishment of a national wages council in June 1971.

Less than a year later, the National Wages Council (NWC) was officially formed on 7 February 1972.

Who Forms the NWC?

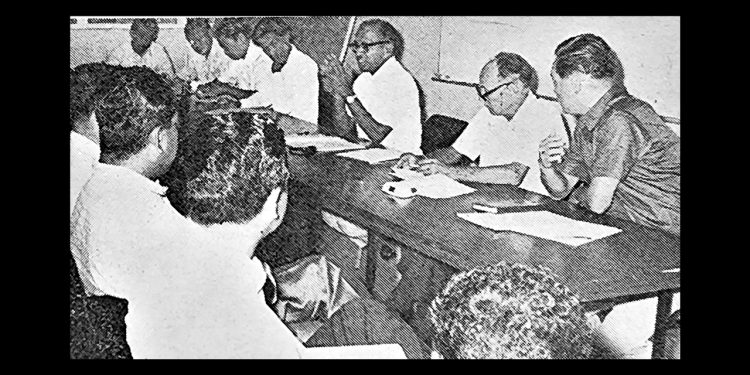

The NWC was and still is, made up of representatives from the Government, employers and trade unions.

Every year, the three parties would come together to formulate guidelines and recommendations on wage policies and salary adjustments that are in tandem with Singapore’s economic performance in the long run.

Though they initially gave more quantitative recommendations, such as the range of salary increments and bonus quantum, today, the council is moving towards more qualitative proposals to allow for more flexible wage negotiations.

So, what would our labour landscape be like if the NWC never existed?

An Unbalanced Workforce

Before the NWC, wage adjustments were informally negotiated according to the bargaining power of trade unions and companies’ management leaders.

Sectors that did well naturally grew, as did their workforce, which gave rise to the bargaining powers of the unions that represented these workers and the wages they could demand.

This is why, going back to the example of the electronics manufacturing sector and the civil service, there was such a huge disparity when it came to wage growth.

If the situation were allowed to persist, this would have probably led to an exodus of the workers within the civil service to other thriving industries.

It may have even led Singapore back to the 1950s to early 1960s when strikes and work stoppages were a common theme in the labour scene.

Ultimately, in the long run, this would have led to the faltering of government-provided essential services such as education and healthcare.

Weathering International Crises

During economic downturns such as the global economic recession in 2007 and the more recent COVID-19 pandemic, the NWC formulated recommendations and guidelines that kept businesses afloat and workers employed.

Given the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, the council believed it better for workers to have a job than no job. Thus, to help sustain businesses and save jobs, the NWC proposed that companies first reduce non-wage costs and consider alternative measures to manage excess manpower, such as sending their workers for training and adopting flexible work schedules.

Employers of workers in the lower-wage group were encouraged to implement wage freezes instead of cutting their wages.

Other measures included tapping on Government support to offset business and wage costs.

Under the NWC’s guidelines, retrenchments were left as a last resort.

Giving Workers a Voice

When discussing labour issues, tripartism is used relatively frequently here in Singapore.

The Manpower Ministry describes tripartism as “the unique collaborative approach adopted by unions, employers, and the Government in promoting shared economic and social goals to arrive at win-win outcomes for all parties in a non-confrontational and objective manner.”

The NWC was one such platform to promote this approach.

It was one of the first official platforms where workers could voice if what businesses proposed regarding remuneration for their workforce was fair. In addition, it was a place where labour representatives could negotiate for better terms.

It was a platform for workers to represent themselves.

Making Singapore What It is Today

Suppose wage negotiations were left to individual trade unions and companies. Negotiations would likely have been left to the bargaining prowess of the two parties, with little regard for Singapore’s overall economic sustainability.

The income gap between workers in different sectors would have been even wider. It would have caused greater manpower imbalance as workers shift to work in industries that pay better, leaving other sectors struggling to fill job positions.

Over the last 50 years, the NWC has helped ensure orderly wage increases, establishing wage guidelines for our economy.

It has helped ensure Singapore’s workforce grow together as one.